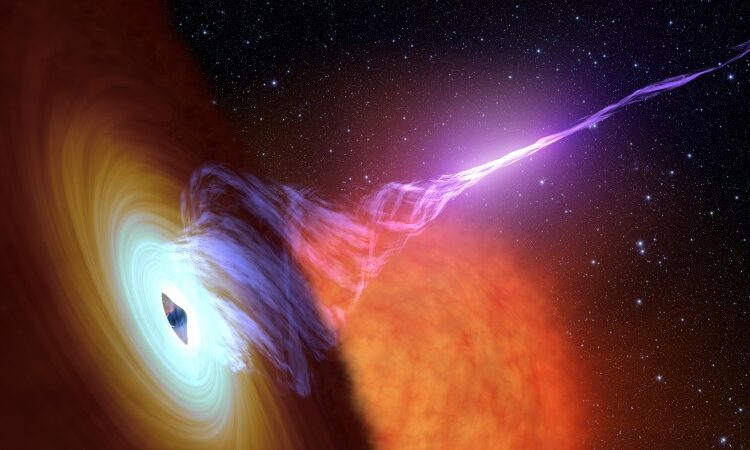

Israeli scientists challenged existing theories about black hole growth and its link to host galaxies by discovering an incredibly hot supermassive black hole covered in cosmic dust using data from the James Webb Space Telescope. With its space-based observatory situated around 1.5 million kilometers above Earth, the Webb Telescope provides scientists with a never-before-seen perspective of some of the universe’s most distant objects and processes.

A group of astronomers led by Dr. Lukas Furtak and Prof. Adi Zitrin from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev examined Webb telescope photos and discovered what initially appeared to be a lensed, quasar-like phenomenon from the early universe. The incredibly bright and far-off objects known as quasars are found in the centers of galaxies. Lead author of the discovery papers Furtak stated, “Three very compact yet red-blooming objects prominently stood out and caught our eyes.” “Their ‘red-dot’ appearance immediately led us to suspect that it was a quasar-like object.”

On the other hand, because of its strong gravitational attraction, stuff falls into and gathers around black holes; this process is known as active deposition. This material may originate from stars, gas clouds, or even other black holes. According to Zitrin, “We used a numerical lensing model that we had constructed for the galaxy cluster to determine that the three red dots had to be multiple images of the same background source, seen when the Universe was only some 700 million years old.”

Working within the context of the UNCOVER initiative, which is surveying the universe with the Webb Telescope, were the Ben-Gurion researchers. “We managed to not only confirm that the red compact object was a supermassive black hole and measure its exact redshift, but also obtain a solid estimate for its mass from the width of its emission lines,” said Furtak, citing assistance from other UNCOVER researchers in the US and Australia. “Gas orbits the black hole in its gravitational field, reaching extremely high velocities not found in other regions of galaxies. The accreting material’s light is red-shifted on one side and blue-shifted on the other due to the Doppler shift, which is affected by the material’s velocity. This leads to wider emission lines in the spectrum,” he said.

Above all, the mass of the black hole is far bigger than that of its host galaxy. “That galaxy’s entire light must fit into a tiny area the size of a modern star cluster. We have fine limitations on the size thanks to the source’s gravitational lensing magnification. One of the study’s co-authors, Jenny Greene of Princeton University, stated that even when all the stars are packed into such a compact area, the black hole still makes up at least 1% of the system’s total mass.

“In fact, several other supermassive black holes in the early universe have now been found to show a similar behavior, which leads to some intriguing views of black hole and host galaxy growth, and the interplay between them, which is not well understood,” she said. “It’s the astrophysical version of the chicken and egg problem,” Zitrin remarked. Currently, we don’t know which formed first, the galaxy or the black hole, or how big the first black holes were or how they expanded.”

- A new version of the Maruti Ignis Radiance Edition has been unveiled at a price of Rs 5.49 lakh - July 26, 2024

- A new set of features has been launched in Google Maps in India, as well as reports about Android Auto incidents - July 26, 2024

- Sanya Malhotra appointed as Brand Ambassador for HMD India - July 24, 2024